I attended a talk last weekend on bilingualism and its effects on cognition as part of the Cambridge Festival of Ideas. As expat parents, my husband and I often talk about bilingualism and what we can do to help our son learn our native language well so that he can become as proficient in Urdu as us.

So I was quite intrigued by this talk. Enough to take out time on a Saturday afternoon for it hoping to find out whether there are any real benefits of bilingualism on children’s development, as well as some pointers on how I could help my son better learn Urdu (and hopefully more languages too).

The talk was organised by Cambridge Bilingualism Network. Panel members included Roberto Filippi (UCL), Ianthi Tsimpli (Cambridge) and Wendy Bennett (Cambridge).

I learnt a fair bit from the discussion so it was a Saturday well spent. And since some Pakistani parents whom I know share similar concerns about their children’s Urdu proficiency, I thought I’d put together a few takeaways from this talk so that they could reach a wider audience.

So here goes.

Multilingual people are not more intelligent than monolinguals.

Several cognitive advantages yes, as well as more developed executive function, but no studies show links between multilingualism and intelligence (intelligence being innate and a more abstract concept than cognitive skills).

Cognitive effects of being multilingual can be likened to the brain going to the gym everyday.

The brain is constantly engaged in making micro-decisions, switching between languages and figuring out which one(s) to repress in response to stimuli. As a result it not only becomes more efficient, but this efficiency also carries over to non-language related tasks.

Multilinguals have a cognitive advantage over monolinguals in focusing on relevant information and ignoring the irrelevant.

They can be faster and more accurate at performing cognitive tasks due to more developed sensory processing abilities.

Multilinguals have a metacognitive disadvantage as compared to monolinguals.

Metacognition is the ability to evaluate one’s own cognitive performance. According to a study, monolinguals are more confident of what they have perceived (no competing voices in their head making them second guess so to speak?).

Multiliteracy brings about significantly more cognitive advantages than multilingualism does.

Multiliteracy involves a greater level of language competence than multilingualism. It includes the ability to read and write in a secondary language. Ianthi Tsimpli shared results of her research which found higher cognitive outcomes for multiliterate children (I couldn’t take a closer look at these as the study is yet unpublished).

Reading in a language exposes you to a much richer vocabulary than just conversing in it. An interesting tidbit she shared was that children’s books contain three times as many rare words (i.e. beyond the 10,000 common words known as the “Common Lexicon”) as compared to everyday speech.

Children’s vocabulary and language ability is linked to socioeconomic status.

Socioeconomic status here is based on the educational attainment of parents, most importantly the mother. Women from higher socioeconomic backgrounds speak more to their children according to studies, which in turn helps them develop a richer vocabulary.

Educational performance of bilingual UK students in standardized assessments at approximately 5, 8 and 12 years consistently lags behind those with English as their first language.

However, this difference disappears or at least narrows considerably in assessments at about 16 years. Bilingual students essentially catch up – the attainment gap is only temporary.

Upon hearing a new word, monolingual children almost always assume that the new word relates to a new object as opposed to an already familiar object.

Bilingual children make the assumption that the new word relates to a new object roughly half the time. Trilingual children do not make this assumption at all. This for me was one of the most interesting things from the discussion. I tracked down the study here.

Knowing multiple languages is a gift. It’s really sad that so many Pakistanis nowadays try their best to not pass this gift on to their children. Instead many view the Urdu language as a mark of shame, baggage they are desperate to get rid of as they try hard to distance themselves from their origins and identity – ironically even while still living in Pakistan.

Children can miss out on the obvious benefits of knowing their home language – familiarity with their roots, the ability to communicate with more people, fitting in with another culture, having in-demand language skills, as well as other pluses which were touched upon in the discussion. Early language acquisition suffers too as children struggle with English unnaturally exclusively forced upon them and in that process end up learning neither language well enough. And then there are numerous other ‘brainy’ benefits of having a different home language too which this talk focused on – if only more people knew.

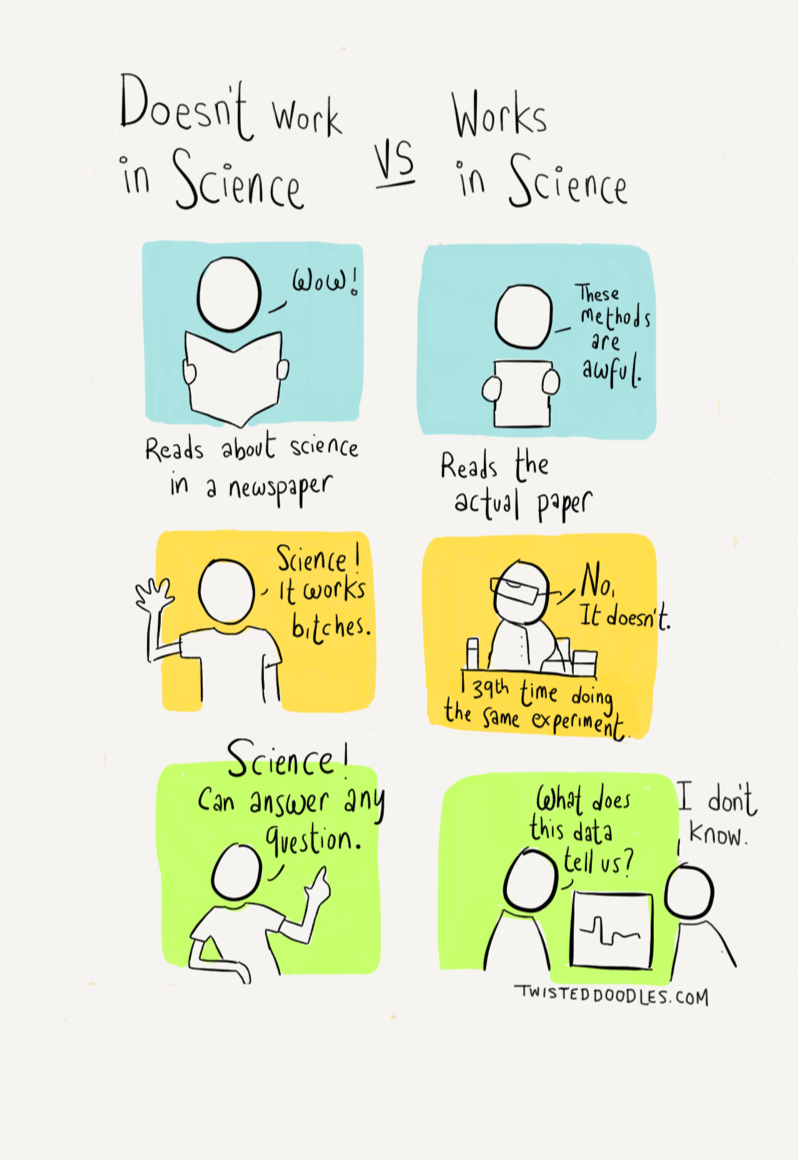

On a lighter note, Roberto Filippi also spoke about how several study findings which are reported by the media are a far cry from the actual conclusions of those studies. For example learning a new language will not prevent dementia as newspaper headlines would have you believe – it may only delay onset. I’ll leave you with a comic by Twisted Doodles which depicts this very well.